In my book The Early Resorts of Minnesota, and my previous blog post on the Jefferson Highway, I mentioned how automobile traffic increased with new highways. This caused Minnesota’s early tourist entrepreneurs to look for innovative ways to flag down motorists and have their location remembered. Flashing neon signs and bright colors helped, but didn’t make lasting impressions. Something BIG was needed. Maybe an enormous sculpture? How about a monster Minnesota fish–or a duck–or a Pelican? Or maybe a legendary character–like Paul Bunyan?

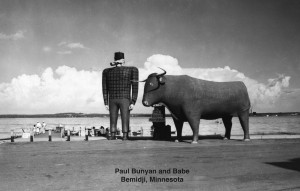

Who can think of Bemidji, Brainerd, or Akeley, without visualizing images of Paul Bunyan? Bemidji’s eighteen-foot-tall Paul Bunyan, with Babe the Blue Ox, is probably the first of the early memorable sculptures to emerge along the highways (a 1940s photo is shown above). Today they continue as popular tourist attractions.

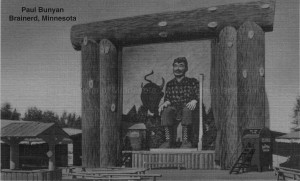

Near Brainerd, a twenty-six-foot high animated Paul Bunyan “speaks” to children by name as they enter Paul Bunyan Land. Built in 1950, the statue and amusement park were moved six miles east of Brainerd in 2003.

In Akeley, the legendary Paul first emerged as a lumberjack in art and advertisements for T. B. Walker’s Red River Lumber Company. (The mill closed and moved to Westwood, California, which carried on the Paul Bunyan legend in advertising.) Since 1949, when Paul’s Cradle was created to commemorate his “birth” (click here for photo), Akeley has been celebrating Paul Bunyan Days (click here for details). In 1984 they added a 25 foot statue of Paul (click here for photo).

In 1950 the 17 foot tall “Lucette,” Paul Bunyan’s sweetheart, was created at Hackensack (click here for photo) and each July the city celebrates “Sweetheart Days” (click here for video).

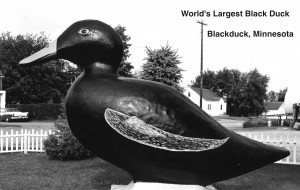

At Blackduck there’s a sixteen foot long sculpture of Paul’s Duck, built in 1942 (shown to the right, and another photo can be seen if you click here).

Other cities followed with sculptures usually portraying some aspect of their real or legendary heritage. Each summer Nevis celebrates “Muskie Days” (click here for info) and has a thirty-foot-long sculpture that was built in 1950 by Warren Ballard. He used wire, cedar, redwood, and concrete.

The city of Erskine has a 20 foot long concrete Northern Pike sculpture, built in 1953 (click here for photo).

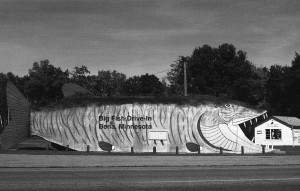

In the 1950s, the small town of Bena advertised the Big Muskie Drive-In Restaurant, (shown to the right). The 65 foot long, wooden walk-in muskie was listed as one of ten most endangered Minnesota landmarks in 2009, but it was rescued by a home town boy, Gary Kirt. (Mpls. Star Tribune, 9-12-09). Bena is also the home of the State Record Muskie.

Alexandria constructed a twenty-five foot-tall granite replica of the Kensington Runestone in 1951 (click here for an old postcard photo, or click here for the museum), and in 1964 a 28 foot tall sculpture of a giant Viking named “Big Ole” (click here for photo).

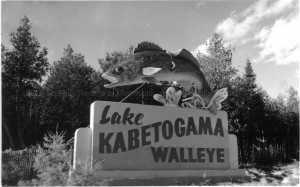

In 1949, a concrete walleye sculpture was created near Lake Kabetogama by Duane Beyers. It was billed as “The World’s Largest Walleye.” Many tourists have had their photo taken while seated on the walleye, which can be seen, with saddle, to the left or click here.

Baudette, too, capitalized on walleyes with the slogan “Walleye Capital of the World.” In 1959, the city built a forty-foot walleye statue on Baudette Bay (click here for photo).

The town of Garrison, on Mille Lacs Lake, also has been called the “Walleye Capital of the World. It has a large walleye sculpture, built in 1965 (click here for photo). On the opposite side of the lake, the city of Isle has a large walleye sculpture (click here for photo).

Rush City has a sculpture titled “The World’s Largest Walleye.” It, of course, was caught in Rush Lake by Paul Bunyan (click here for photo). Incidentally, according to the Department of Natural Resources, the largest real walleye caught in Minnesota weighed seventeen pounds, eight ounces, and was taken from the Seagull River at the end of the Gunflint Trail in 1979.

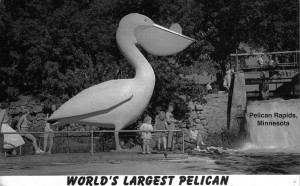

International Falls has a 26 foot statue of Smokey the Bear, built in 1953 (click here for photo) and Pelican Rapids has a fifteen-foot concrete pelican sculpture built in 1957 and billed as the “World’s Largest Pelican” (photo to the right, or click here for others).

Some of the early roadside attractions might be considered Folk Art, and may ignore traditional rules of proportion. But in the eyes of the beholder, the strange proportions made no difference in their popularity or longevity; Bemidji’s Paul Bunyan looks just fine, remaining the same since 1937.

Today the counterparts of these early sculptures are numerous and cover every topic from giant strawberries to life-sized dinosaurs. They are found everywhere, from gas stations and fast food restaurants to theme parks and chambers of commerce. The most recent ones are made of fiberglass, with some transported from as far away as China. Wherever they find a home, they draw attention and cause travelers to smile, stop, and hopefully retain happy impressions of their travels in Minnesota.

If you have a unique story about tourism or early resorts you’d like to share on my blog, click here to submit it for consideration.